Context graphs have a problem that deserves more attention.

The promise of context graphs is to capture decision traces, build organizational memory, and preserve the reasoning behind every choice so the company learns from itself.

Great read (part 1 and 2) both

The article above from @parcadei is a great read on the main problems of achieving the ideal context graph.

Getting inside people's brains to capture how they actually make decisions is nearly impossible. You can record what someone decided. You can even document the inputs they considered. But the reasoning process itself? The pattern matching, the intuition, the judgment calls that happen faster than conscious thought? Traditional software has no way to capture that.

But at the same time, Cody Schneider, founder of Graphed, absolutely nails how I think this all connects and will work…

Cody's right. You're not going to build the perfect context graph. No one has a perfect knowledge graph either, and that's fine. Perfection isn't the goal.

Employee-built agents are changing this dynamic in ways that context graph proponents should take note of. Because it’s the only way I see this working.

When You Build an Agent, You're Encoding Your Decisions

Here's what I find interesting. When employees show up with their own agents, those agents share what they're doing without exposing proprietary data. Every agent someone builds contains a piece of their reasoning process.

This is decision-trace capture that SaaS software never achieved.

I wrote about this in "Complete Context Graphs and Why Memory Needs to Forget" earlier this month.

The piece explored how context graphs work alongside knowledge graphs, how selective memory determines what persists, and how external context matters just as much as internal decisions.

What I didn't fully appreciate then was how these decision traces would actually get captured. Traditional enterprise software captures the what. An agent captures the how, or at least the structure of it.

When a salesperson builds an agent to research prospects before calls, they're encoding their preparation workflow. When a finance analyst builds an agent to summarize weekly data, they're encoding what signals they actually care about. When a support lead builds an agent to triage incoming tickets, they're encoding years of pattern recognition into something the organization can observe.

An agent doesn't capture the intuition itself. Pattern matching still occurs in the person's head when they design the workflow. But the agent makes the structure of their process visible. You can see the prompts, the sequences, the priorities. That's more than any enterprise software has ever surfaced about how individuals actually work.

The Excuses Have Evaporated

Two weeks ago in "The Broken Pool Cue," I argued that AI adoption has become a test of will, not technical ability.

With tools like Claude Cowork, the technical barriers that kept people on the sidelines have disappeared. You don't need to understand terminals. You don't need to configure development environments. You show up and start building.

Cowork is the door opener. For people nervous about command-line interfaces and IDE configurations, it removes those obstacles entirely. You can build agents, maintain context across sessions, and watch AI handle the technical complexity.

Cowork isn't the whole story. Claude Code remains the full power tool for those ready to go deeper. What matters is that Anthropic has created an on-ramp that makes the first step accessible to anyone willing to take it.

From Workarounds to Native Features

I've been building a book author agent over the past few months. The workflow spans chapter outlining, Kindle formatting, and cover art generation. It's the kind of multi-step, multi-domain project that would have required coordinating several different tools just a year ago.

I started using a Claude Code approach called Ralph Wiggum last weekend. It's a workaround for maintaining long-running agent sessions. It worked, but it left me wanting more control for something as complex as book production.

Then, Claude Code Tasks launched. One week later.

I'm switching this weekend. Tasks feel more controllable, though I'm still exploring the boundaries.

This is the pace we're dealing with now. A workaround I built seven days ago is already being replaced by a native feature. The tooling keeps accelerating.

Jobs to Be Done

Clayton Christensen changed how I think about problems with a single insight. People don't want a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole.

When you focus on the drill, you optimize the tool.

When you focus on the hole, you optimize the outcome.

Most enterprise software gets this backwards, building better drills instead of asking what holes people actually need.

The Jobs-to-Be-Done framework applies directly here. The question for every employee becomes straightforward. What job do you want AI to help you do?

You might research blogs to stay ahead of your industry, organize meeting notes into actionable summaries, prepare week-ahead briefings that surface what actually matters, or write chapters for the book you've been putting off for years.

Each of these jobs, when translated into an agent, encodes decisions. Which sources do you trust? What signals indicate urgency? How do you structure information for your own comprehension? The agent becomes a record of your judgment.

This is why companies should care about employees building their own agents. Not because it creates efficiency gains, though it does. Because it creates visibility into how decisions actually get made.

The Counterargument Loses

The alternative approach is obvious. Companies build their own agents and force employees to use them.

The logic seems sound. Centralized control brings consistent processes and easier compliance. But this approach captures only what IT assumes about how work should happen, not how it actually happens.

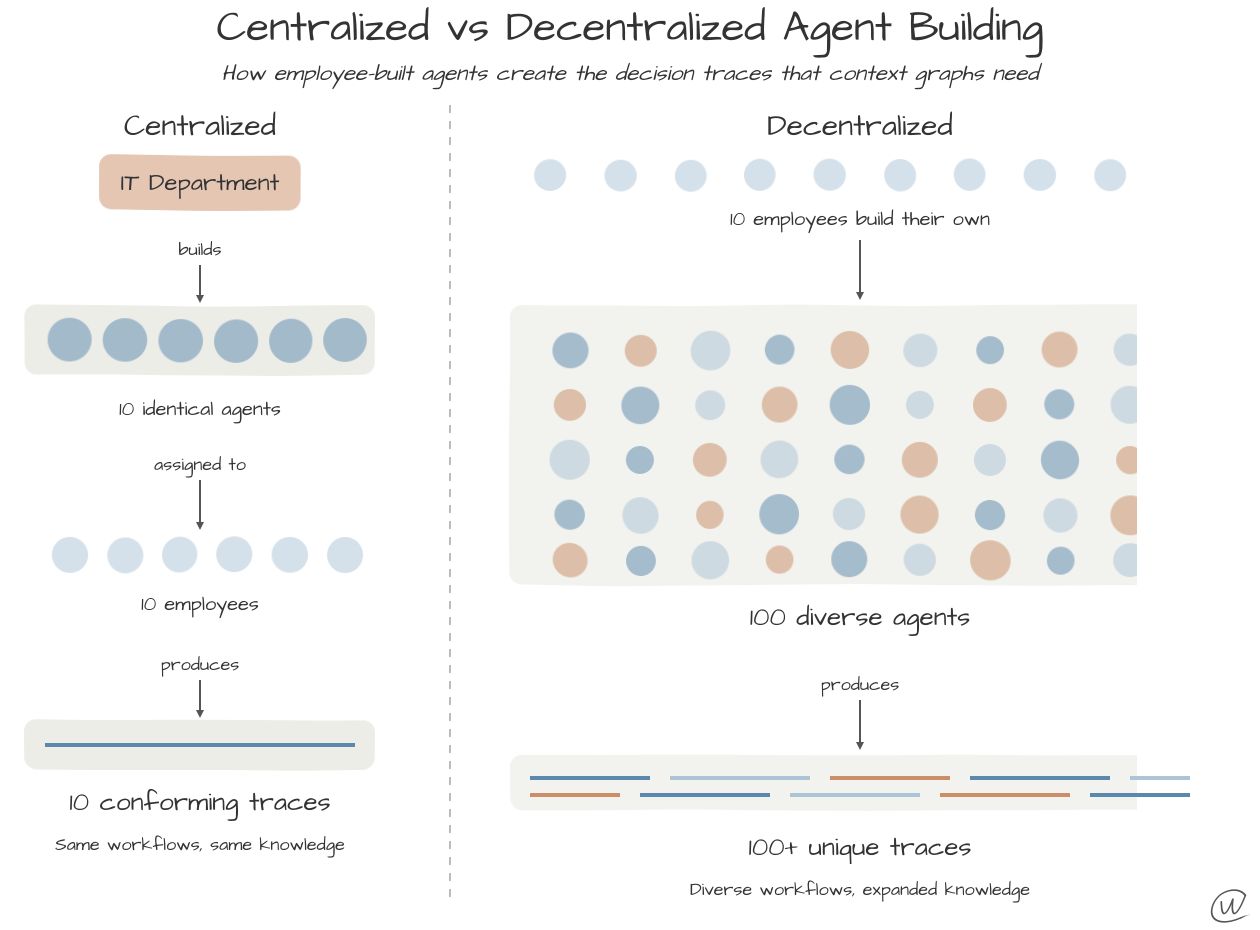

Consider two scenarios.

In the first, 10 employees are told to use 10 agents built by the IT department. They conform. They follow the prescribed workflows. The agents capture exactly what IT encoded into them, which is IT's understanding of how work should happen.

In the second, 10 employees build 100 agents to solve their specific jobs. Each agent reflects actual working patterns, encodes real decision processes, and surfaces knowledge that management never knew existed.

How employee-built agents create the decision traces that context graphs need

The centralized approach fails to expand knowledge in the same way. The conforming users generate conforming traces. The agent-building employees encode decision traces that nobody at the top could have specified in advance.

Decentralized wins on knowledge capture, though it does require some governance thinking.

When an employee leaves today, much of the knowledge of how they did their job goes with them anyway. Agents don't change that. What they do offer is an opportunity to make that knowledge visible before it walks out the door. Organizations can request, as part of employment, that agents encode the process. That's a protocol waiting to be written.

Many employees are already building agents on nights and weekends to streamline their own work. The only difference is whether organizations acknowledge it. The instinct to make agentic processes SaaS-like, to centralize and control them the way we did with software licenses, misses what makes them valuable in the first place.

Where to Start

If you've read this far and you're still on the sidelines, the path is clear.

Start with Claude Cowork, Google Gems, or ChatGPT with custom instructions.

Watch Anthropic's research videos on Cowork to see what's possible. The interface is designed for people who want to build without getting lost in technical complexity.

Cowork is the best way to see this in action. It's not the only way, and it may not be the final destination. It is the accessible starting point that removes every remaining excuse.

Every agent an employee builds makes their expertise visible.

The process that used to live only in their head now exists as something the organization can observe, learn from, and build on.

That's the decision-trace capture that context graphs promised. It's just not coming from the software vendors.

And it's happening with or without organizational permission.